![]()

by Michael Matza

Inquirer Staff Writer

The death of the deposed Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi unleashed volleys of celebratory gunfire in Tripoli and a muted and no-less-joyful response 5,000 miles east, among the estimated 200 expatriate Libyans living near Philadelphia.

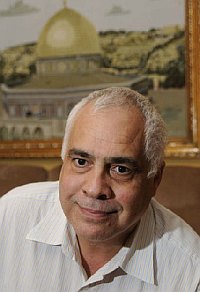

“I have been monitoring and following Libya all my life,” said Osama Al-Qasem, 56, who left the country as a child and lives in Holland, Bucks County. “My father was a lawyer. Life was very pleasant until Gadhafi came to power.”

Although Al-Qasem was just 12 when he left for boarding school in England, he recalls how the promise of the 1969 coup that began Gadhafi’s reign quickly soured:

“He was good in the first year or two, then . . . a screw went wrong in his head and he started doing stupid things.”

Enamored of the Little Red Book teachings of Mao Tse-tung, Gadhafi created a guide he called the Green Book, and his edicts, Al-Qasem said, became increasingly bizarre.

Gadhafi said small houses should belong to small families and large houses should belong to large families, and he forced families of different sizes to swap.

Libyan TV channels blared day and night with his picture accompanied by scenes of cheering crowds.

People were permitted to withdraw only small amounts monthly from their bank accounts, making it hard to maintain even a middle-class standard of living.

“Popular committees,” made up of workers, were appointed to run the factories they worked in, often leading to mismanagement.

In an effort to make Libya’s food supply self-sufficient, he ordered residents “to keep chickens on their balconies and sheep in their gardens,” Al-Qasem said. “He took Libya from an oil-rich country to a very poor and empty kind of place.”

As Gadhafi’s reign wore on, Al-Qasem said, “he would come to [Arab League] meetings looking like a comedian. Fashion-wise, he was amazing. His [clothing] choices were out of this world.”

Happy that Libya can now start a new era, Al-Qasem is also apprehensive about what comes next.

“I am concerned,” he said, “that [the transitional government] understands what democracy and freedom are. To allow people to express themselves. To respect each others’ opinions. To work together and not allow their personal tribes to get in the way.”

Amin Elarbi, 61, a Libyan-born dentist with a home and practice in King of Prussia, left his homeland in 1981. He returned for the first time last month for a short visit with family members in the rebel-controlled eastern province of Benghazi.

“I supported the opposition groups all these years, fighting this regime by peaceful means,” he said. “Finally, I felt the country was safe enough to go back.” He flew to Cairo and traveled overland.

He was in his late 20s when he left Libya to attend the University of Pittsburgh. He moved to Philadelphia in 1988 and trained as a dentist at the University of Pennsylvania.

When a friend called Thursday from New York to say Gadhafi was dead, Elarbi and his wife, Amal, who works at the Vanguard Group, contemplated playing hooky to celebrate “the end of a dark era.” But duty called and they went to work.

Though cautious about what lies ahead, he is optimistic:

“Some of my friends, who studied in the States, are in executive positions with the National Transitional Council. I feel confident they will do a good job. We have to give them the opportunity to put things together.”

Elarbi and a handful of Libyan expatriates meet monthly for casual get-togethers at one another’s houses. The last meeting was in Allentown.

“I promised them,” he said, “that if Gadhafi falls down, the next party will be paid by me.”

But the revelry will have to wait. Elarbi leaves this weekend for a pilgrimage to Mecca.

When he returns from Saudi Arabia in about a month, he said, “we will celebrate Thanksgiving and the liberation of Libya.”