by Jacob Bender, CAIR-Philadelphia Executive Director

I awoke yesterday morning to hear the news on the radio that Bob Dylan had been awarded this year’s Nobel Prize in Literature. To many in the post-war baby boomer generation, I am sure this news was met with near-rapturous joy, as it was by me.

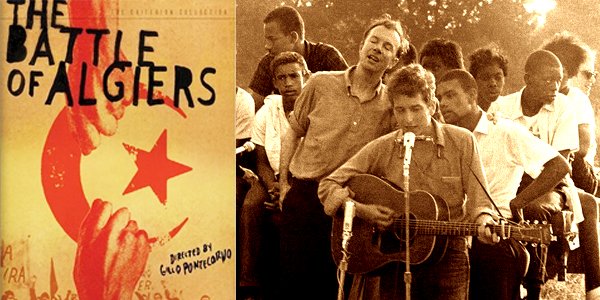

Dylan’s words and music were the soundtrack for the whole tumultuous decade of the Sixties — his words perfectly and ecstatically capturing the zeitgeist (“spirit of the age”) of sudden cultural and political change unfolding before our eyes. No more so than in “When the Ship Comes In”, a paean to prophetic transformation, which Dylan performed at the famous March on Washington in August 1963 where Dr. King delivered his stirring “I Have a Dream” speech.

If Muhammad Ali was my generation’s hero and the collective embodiment of our dreams of physicality, Dylan was our collective conscience: the voice of a generation signing out against racism at home and the War in Vietnam abroad. In the songs of his early “political” career, Dylan was clearly channeling the Bible and its prophet’s thundering for social justice, denouncing the hypocrisy of the rich and the powerful (see: “He’s Only a Pawn in Their Game”, “Masters of War”, “The Times They are a Changing”, “Blowing in the Wind”, and “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll”.)

Yet Dylan, never one to follow the scripts others would hand him, would, by 1966, turn his back on the “protest song”, and turn to a more intimate and romantic style, best realized in his classic album “Blonde on Blonde”. If Dylan had written nothing else after 1966, he still would, in my opinion, be one of the great American writers of the Post-War Era.

In the year 1966 — 50 years ago this week — I was sitting in a movie theater in Los Angeles (my home town) watching the just-released film “The Battle of Algiers”.

It is a film that would change history and inspire millions around the globe. Directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, an Italian Jewish leftist filmmaker, the movie chronicles the revolt in the city of Algiers by the National Liberation Front against the occupying French colonialists. Nearly 2 million Algerians would die between 1954 and 1962 during their struggle to gain independence from France.

Beyond its political importance, “The Battle of Algiers” is an amazing work of art for two reasons: First, it utilized only a handful of professional actors in the film; the remainder of the cast, dozens of speaking parts, were Algerians from all walks of life, many of whom had participated in the events dramatized in the film. Second, the scenes in the film appear so realistic, and so close to newsreel material, that the producers of the film were obliged to begin the film with a declaration that “No newsreel material was used in the making of this film.”

The issues dramatized in “The Battle of Algiers” are still as morally relevant today as they were fifty years ago:

- The destruction caused by colonialism;

- The hypocrisy of the West when denouncing Third World resistance;

- The ethics of torture by the French, and

- The utilization of indiscriminate terror by the Algerian resistance.

To celebrate its 50th Anniversary, “The Battle of Algiers” is now in limited theatrical release, which affords you the rare opportunity to view it on the big screen. The film is currently playing at Ritz at the Bourse. View the trailer on YouTube.

These two masterworks of the human imagination — the poetry of a songwriter, and a film dramatizing a nation’s fight for its freedom –- allow us to see the power of art in the betterment of the human condition. It is a lesson to be remembered in our own struggle against Islamophobia.